Although the process of tie-dyeing is wide open to artistic interpretation, some aspects are non-negotiable. The fabric must be cotton. The dye must be Procion®. If the fabric’s new, you must wash it, then pre-soak it in soda ash so that it can be “activated” and accept the dye.

Folding your material back and forth can create alternating, interesting patterns.

Was there a connection, in fifth-century Peru, between indigenous music and the emergence of patterned, colorful, tie-dyed fabrics? When tie-dye came back around in the 1960s there certainly was. Author Ken Kesey was part of the first government experiments with LSD (which helped inspire him to write One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and soon afterwards he formed a kind of benevolent gang called The Merry Pranksters. This boisterous entourage of counter-culture characters included Beat icon Neal Cassidy (aka “Dean Moriarty” in On the Road) and a new hard-to-categorize musical group called The Grateful Dead. The ’Pranksters kickstarted the psychedelic movement of the sixties during a road trip to New York City in 1964 to celebrate the release of Kesey’s second book and attend the World’s Fair. More importantly for the world of fashion, they are credited with bringing tie-dye out of obscurity and directly into the epicenter of nascent hippie fashion. They made it, they wore it, they even painted their bus— named Further — in swirling, tie-dye patterns. “You were either on the bus,” the saying went, “or you were off the bus.” A line of sorts had been drawn across society, and wearing a tie-dye connected the wearer, with invisible threads, back to that original bus.

About half of the houses in our Wilmington, NC neighborhood have some kind of flag sticking out of their fronts. These textiles function like a one-word synopsis of the clan’s ethos, a lone utterance from the property itself. Messaging from them is direct and basic. “NC State,” one type declares. “UNC” brags its neighbor. “America!” chants every other. Maybe our family should get a planet Earth one. Who could argue with that? What if it united the neighborhood, reminded us that we’re on the same home team? What about a social justice one, or BLM sign?

Would the Coltons, our Trumpy Texas neighbors across the street, see it as a provocation?

Entering my kitchen I interrupt a scene in medias res. Betty Colton is explaining something important to my wife, Isabel. Everyone behaves when she’s over. The dog sits.

There is mention of pants and patches and sewing and my ears prick up when I hear her mention tie-dye. My connection to whatever she and my wife have been planning will have something to do with my favorite of the textile arts. Odd, because Isabel had issued a moratorium on my time-consuming tie-dyeing until we patched some holes in the walls. Betty’s charm must have shuffled her chore hierarchy.

“Did Isabel mention to you that we had talked?” Betty’s West Texas accent could butter biscuits.

She had not. But I don’t tell her that because high fences make good neighbors, and we have a good thing going: mutual politeness and smiles and our three kids love them.

Like a developing photograph the plan is revealed to me. Betty will patch a bunch of Max’s pants and I will tie-dye a batch of clothes for her grandkids’ photo shoot. It is a settled matter. Isabel says we’ll be glad to do it and I note that “we” is doing a lot of work in that sentence.

Betty thanks me, and I’m struck by the lingering eye contact and in a sweet tea, fleece-wrapped guardrail kind of way she reminds me that Ineed to have them done and returned to her in time to sew them for a photo shoot on June 13th. It’s early May now.

That’s June, she reminds me. The 13th.

Mix one cup of soda ash into one gallon of water and soak the fabric for twenty minutes. Wring it out. This simple, straightforward step prepares the cotton fibers to receive the dye, makes the result unquestionably more vivid and permanent. But I’m so pathologically anti-authoritarian that I doubt the exactness of the instructions and play Devil’s Advocate with Space and Time. Does it really need to be twenty minutes? How about a gallon and change?

It’s mid-May. That’s tons of time, which is the kiss of death for a procrastinator like me. Betty’s husband of almost forty years, Benny, told me that when they lived in west Texas she was a national sales rep for Singer sewing machines, and the more I talk with her the more I realize that this kind, helpful woman must have been a killer salesperson. I reaffix June 13th to the front of my mind.

I got my grandfather’s hair, name, and some of his coin collection. He once yanked his money back out of the Sunday collection plate when he found out it was for missionary work and I think I got some of that, too. Most of what I hate about organized religion comes into sharp focus when I think about the driving purpose behind a damn mission trip.

If I had to be a missionary, though, I’d spread the gospel of Jerry Garcia. No, seriously — why not? The late Grateful Dead frontman was a God to hippies, or at least a prophet, and as a teenage fan I consumed “bootleg” tapes of live concerts like a sacrament. They worked potent magic on teen me: loud, hissing cassette tapes unleashing bottled lighting, right there in my smelly room.

Right around the time I was discovering Jerry through my first few Grateful Dead tapes, the very public meltdown of our preacher signified the end of my tolerance for Christianity and made me sad in a way that could have only happened if a little part of me was rooting for all of it to be true. But instead, one Sunday, he took out an orange and stared at it, asked us how we knew it was an orange, and then started peeling it, asked us if we still knew it was an orange and started eating it, asked us, between slurps, something else and then broke down, sobbing, and said he couldn’t do it anymore. He walked out of the pulpit and kept going. Turns out he was actually a terrible alcoholic, and I immediately wanted all those hours returned to me which I had wasted in that church.

Jerry was an addict too, but it was a more open secret.

It’s a warm day past the midway point of May and two thirds of my kids are catching lizards with Benny in his back yard. When I head across the street to get them, Betty casually pokes her head out the front door and thanks me again for the project I haven’t begun.

Starting is harder if you haven’t done it in a while, so I change the subject to how lucky we are to have them as neighbors. She dismisses her excellence with a wave. I mean it, though. Whenever Ollie goes missing, it’s because he wandered out an unlocked door and made a beeline for Benny and his swooping-up arms and garage full of tools and machines. Whenever Benny sees them in our front yard he keeps them safe from traffic. When the kids make it across the road, Benny and Betty fall into routines with each child. Benny lets Ollie feed his chatty grey African parrot seeds and feed himself sugary snacks; Betty shows Lucy how to hold their youngest grandchild; Benny gives Max an old Rubik’s cube to solve and a mouse trap to fix. When we need to replace the screen door or puppy-proof our fence, Benny appears like a general contracting angel to help us.

A few cautious months after moving here we let Max go over there by himself, and one day he came back talking about Donald Trump.

“Benny says Trump did some good things for America,” Max announced one day, flicking the kill bar on a mouse trap.

“They have a picture of Trump in their house,” he said on another.

I’m avoiding the discussion, like I avoid the unfixed holes in our wall. Benny and Betty could make the difference, one day, between the kids living or getting hit by a car. Also, they are sweet as can be… to us outwardly cisgendered, hetero white folk. Benny calls me “brother.” I wonder how much they perceive of our atheist, Jewish, hedonistic, hippie, antifa stripes, but I suspect that they do suspect… and love us regardless.

But I don’t talk about that stuff with them because I know we’re one conversation away from a burnt bridge, and that’s just how it goes in 2022.

Betty comes back outside with a large plastic bag, and when she holds it up I see the shirts and onesies and swaddle blankets pressing against the inside like the contents of a distended stomach. She asks about Max’s pants. She needs them to square the deal, so I promise to go get them from across the street, then ask about what colors and patterns she wants for her dyes. Her answer is complicated enough that I wish I had started writing it down, and once she’s too far into it for me to stop her I can only nod. Echoes of her jet-setting Singer Sewing Machine sales rep days reverberate into our current business conversation, and as we plan patterns and colors I’m slightly intimidated.

“Got it,” I confirm.

Prepare the dye in small bottles. When I first started tie-dyeing I used official tie-dye bottles made just for this purpose, but in hindsight that was uptight and nerdy, so now I’m proud to use whatever small bottle I can find and drill a hole in the cap. I add roughly double the suggested amount of dye, because unless I’m doing a pastel batch nothing ever gets as bright as you want it. The color fades so much after rinsing and washing. Beginners do need to brace themselves for this disappointment. Some powder sticks to the bottom of the bottles and must be stirred around. The powder’s so cinnamon-fine it defies physics, presses against the walls of the bottle like an escaped prisoner avoiding the searchlight, clings to itself around an impossibly dry core.

In June of 1993 I found myself at my first Grateful Dead concert, unaware that my attendance will later give me entrée to a dwindling circle of people who ever saw Jerry Garcia live. I was meandering solo, looking for my two classmates among a crowd of forty thousand, when the music started and locked me into it. Even though Jerry was so far away he might have been a wobbly mirage, he made eye contact with only me, over his glasses, and exchanged a knowing look that sparked like the finger-space between God and Adam.

The more meticulous you are in this last pre-dyeing step, the better the shirts will turn out. For accordion folds, mandalas, starbursts, and concentric circles, you will be using string. For spirals, bunches, and splotches you will be laying the garment flat and trying to keep all the creases the same size before rubber banding it. Some tie-dyers use tweezers here, to make folds consistently less than an inch high. This effort pays off by reducing the amount of white, undyed fabric when unfolded. This is good because when you’re rinsing out the excess dye at the end, any white space gets tainted with the runoff anyway. White cannot stay white.

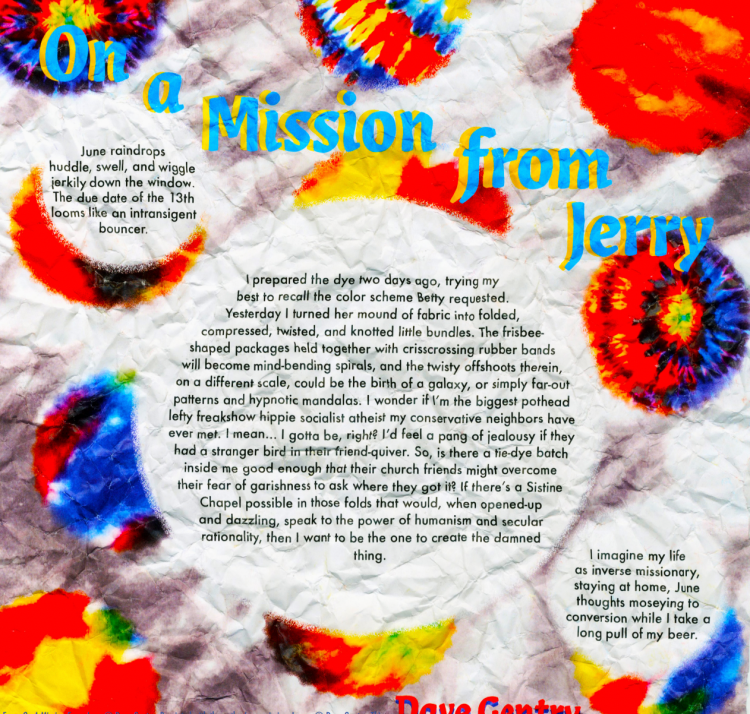

June raindrops huddle, swell, and wiggle jerkily down the window. Cornered into the garage by the weather, the children are practically on top of me “helping” with the next step of tie-dyeing. Despite getting in the mood with music et al, I’m detecting stress in my system; the due date of the 13th looms like an intransigent bouncer.

I prepared the dye two days ago, trying my best to recall Betty’s color scheme. Yesterday, I turned the mound of her fabric into folded, compressed, twisted, and knotted little bundles. The frisbee-shaped packages held together with crisscrossing rubber bands will become mind-bending spirals, and the twisty offshoots therein, on a different scale, could be the birth of a galaxy, or simply far-out patterns and hypnotic mandalas. I wonder if I’m the biggest pothead lefty freakshow hippie socialist atheist the Coltons have ever met. I mean… I gotta be, right? I’d feel a pang of jealousy if they had a stranger bird in their friend-quiver. Is there a tie-dye batch inside me good enough that their church friends might overcome their fear of garishness to ask where they got it? If there’s a Sistine Chapel possible in those folds that would, when opened-up and dazzling, speak to the power of humanism and secular rationality, then I want to be the one to create the damn thing.

I imagine my life as inverse missionary, staying at home, June thoughts moseying to conversion while I take a long pull of my beer.

Concert revelations aside, Jerry was probably not the savior of mankind… although I do believe he was a kind of prophet. Sounds crazy to hear myself say something like that, but I’m joined in this feeling by legions of heads who truly listened to improvisation and mythology unspool from him. I only knew him through his songs, which had conducted a counterculture movement across the changing landscape of America a decade before I was born. His sound itself was a kind of patchwork, an all-American tie-dye of sorts: Harlem Jazz and Delta blues and Nashville country and dust bowl folk, swirling like unique fingerprints every night. Setlists rotated and song versions mutated so that no two concerts were ever the same; fans who were there (or heard the tapes) parsed the minutiae of the shows afterward like holy desert sermons.

Legendary concert promoter Bill Graham commented that the Grateful Dead weren’t the best at what they did, but they were the only ones doing it. When Jerry Garcia was asked to explain the appeal of the Grateful Dead and the intense devotion of its fan base, he said his band was like licorice.

“Not everybody likes licorice,” he mused, “but the people who like it really like it.”

Apply the dye. Get in the folds. Don’t leave any white space. Put a different color on the back than the front — where these two meet will be some cool effects. Start with lighter colors and see what happens when two colors overlap. This is the darkest the fabric will ever look, and no one knows for sure what the pattern will look like until tomorrow, when you open it.

The answer to the question, “What Would Jerry Do?”, which no one would ever think to put on a mawkish bracelet, is complicated. The answer might include heroin. He had his demons, but as a cultural icon he refused to make an idol of himself. He had a hard time calling in favors, and sheepishly asked his manager to get him the occasional seat in a popular restaurant. He was overweight and shy and shaggy and, until you heard him play, you might consider him an unlikely candidate to be a rock star. Oh, that makes me love the big man more.

It’s after midnight. I push up my glasses with my shoulder and then take off the first latex gloves with the palm-pinching move I learned in the pandemic.

Cover the fabric with plastic and don’t touch it for 24 hours.

When I go inside I notice that my fingertips are all different colors and realize it must have happened after I peeled off the surgical gloves, when I cajoled a few straggling swaddle blankets back onto the wire. Touch this dye once, and it stays on your skin for days, although I secretly like it when my fingers look like this. For the foreseeable future I’ll smile when I look down, perhaps remembering the Confucius quote about the most faded ink being stronger than the most vivid memory.

Twelve hours later, when the kids have complained about their poorly-made lunch and the rain, I make an executive decision that we should open up the tie-dyes early. I dare not say this aloud to Max, Lucy and Ollie until I have rinsed all the excess dye out of the promising little bundles — they will be unhelpful during this annoying but necessary step. But they find me, and three heads press into the tiny space over the sink where I’m squeezing and squeezing. They ask what I’m doing while I’m wringing and wringing until my hands get crampy and then I answer a fraction of their questions. I ask them not to touch the other dyes on the floor and count to a hundred more squeezes before finally officially resurrecting the childhood carpal tunnel syndrome that never really died. This is the last step before we open them, which is the grandest reveal, the moment of truth. It’s also the darkest and most vivid the things will ever be.

The parking lot scene before a Grateful Dead show was like its own country, a perpetual carnival with a mayfly lifespan at each stop of the tour. It had its own language, food, music and currency. Trading, the black market, scoring, hustling… all flourished in the wide-open vending scene alongside traditional monetary exchange in this glinting, temporary environment. The band controlled what happened inside the venue, but a several-block radius around the venue was all ours. A large portion of us had on a tie-dye. A large portion of the merchandise had Jerry’s likeness on it. The bushy beard. The glasses. The eyes behind the glasses. Legend. When the post-show dust settled there was a sense of a before and after; the experience and its audio recording were folded into the rest of history like a new object of cognition, or like a tie-dye.

When I arrive with six gloves, six stained hands are already in the garage poking at the rinsed-out and colorful lumps. I start with Ollie, and he jams all his digits into one finger hole. An adjustment later, I help Lucy get hers on. By the time I get to Max I am shocked: he has put both gloves on successfully.

We look like back-alley surgeons. We get to work on the first bundle. A spindly cotton tendril — possibly a swaddle blanket —is wrapped in so many rubber bands I stop trying to save them in a separate pile and reach for the scissors. Max is using them to try to cut a notch in the plastic table. I ask him to stop. I’ve got the dripping cloth half opened in one hand and my other hand out, waiting. I ask again but he’s focused on that notch, and I imagine his ADHD medication working to deliver my message to his brain. My patience is waning, and we’ve only just started. It gets quiet and he sees Lucy and Ollie and I, all waiting on him. I decide that in three seconds I’m going to invoke Betty’s name, or Benny’s. I don’t have to. He puts the scissors in my hand, and I remember to thank him and finish cutting opening the new dye.

We share the first glimpse, collectively breathtaking.

“Oh. My. Gosh!” I gush.

“Gosh…” Ollie copies.

This is, by far, my favorite part. I point out lovely little details.

“See where the yellow mixed with the turquoise on that part?”

Oohs and ahhs. I love when they get into it.

“This part looks like an owl.”

“I see an alien!”

“Maybe you’re both right.”

“Gosh…”

The plan is to drip dry them, and despite the light rain starting, our entire front yard is soon covered with tie-dyes. I am beyond delighted with our own wet freak flags, a bold pivot for our lawn from its workaday business casual greenness to this alter-ego psychedelic persona. The rain, I hope, is washing out the last bit of dye without making the patterns bleed too bad.

Betty pokes her head out of her house, and yells something encouraging. With our property functioning like a kaleidoscopic come-hither message, she crosses the street. Because they have blurred a little in this rain I’m suddenly immensely self-conscious of my dyes and I don’t want her to actually see them before they’re ready.

She expresses appropriate awe at the quantity of colors and patterns. I’m listening for traces of disappointment.

She tells me I did a great job.

I demure, noticing our place looks like a yard sale.

She points out the parts here and there that she really likes.

I unfurl, tell her the gist of how some were made.

The tiniest hint of a cloud crosses behind her eyes and she suggests maybe she should have sewn the tops to the skirts before dyeing, eh? A little late, I catch her meaning. She wanted there to be continuity in the batch. I’ve got shirts doing one thing, and a long bolt of fabric, soon to become two skirts, doing another. I’ve got swaddle blankets and onesies each doing their own thing. Tie-dye is unpredictable, like the Dead, like jazz, like improv, man. It’s not a studio album! I’m not sure I can keep tone out of my voice if this goes sour, but I say I see what she means now, and I hope they’ll be all right.

Oh, of course they’ll be all right.

I should have paid more attention to her color requests.

They’ll be fantastic, she exclaims. And she turns her attention to the kids as they pour out of the house, leave the door open, and tell her all about how much they helped.

Wash on low with Synthrapol®. This special detergent helps lock in the color. Change, at this stage, is unwanted.

Dried and folded, the cosmic cinderblock rests on the dryer like a hard-earned stack of animal pelts. I bring the kids across the street with me to drop them off, but no one answers the door. On the Colton’s porch, trespassing, holding gifts meant in some way to convert, I imagine I’ve been sent by Jerry Garcia himself, on a mission from the Grateful Dead to save humanity. I’m armed with onesies and swirls and vortices and consciousness-provoking patterns that might cause a person to reevaluate their life choices, or at least turn off Fox News. We leave them on a wicker bench.

One day in 1965, back when his band was called The Warlocks, Jerry Garcia was smoking DMT when he saw something life-changing in a folklore dictionary. The room full of musicians and friends was trying to think up a new band name, and he was on a solo trip under the influence of this wildly intense and shockingly short-lasting hallucinogen. His spiraling attention lingered on the book’s entry for “Grateful Dead,” a folktale in many cultures of a deceased person bestowing great benefits — from the “other side”— upon a kind stranger who helps to bury their remains. Jerry liked that idea. He died in 1995, almost thirty years later, and the band would continue playing, in various iterations, almost thirty more years after that. I could never shake the idea that whatever guitarist they put up front in his spot was helping to bury him.

Back from the photographer’s, Betty is cradling her sleeping, tie-dye-wearing granddaughter on the couch. In the muted living room light, she indicates the baby’s outfit and stage whispers, “Oh my stars!” Through the window I can see flashes of the grandson’s tie-dyed shirt while Benny chases him and Ollie around the bushes. Max and Lucy have plopped down on the carpet inside, taking advantage of the grandson’s toys. Betty is excited to tell me, with her free hand now clicking off Fox News, how precious the tie-dye outfits looked in the photo shoot.